If such indignant subtext seems ill-fitting for a down-and-dirty gangster flick that’s due to the potency of the script. Writer John Sayles is now a revered left-wing indie film-maker whose work, including Matewan (1987) and Lone Star (1996), frequently highlights the plight of under-the-radar communities. He used the money writing sly genre takes for Roger Corman’s New World Pictures to kickstart his own movie-making career with zero-budget Big Chill-alike debut Return of the Secaucas Seven (1980).

Inbetween the hilariously entertaining monster rampages of Piranha (1978), Alligator (1980) and The Howling (1981) in his Corman years, The Lady In Red stands as Sayles’ pulp fiction Grapes of Wrath, the Steinbeckian liberal rage at an unjust society screaming off the screen.

Such righteous anger no doubt delighted the movie’s behind-the-scenes Svengali. Although his name doesn’t appear on the credits, in many ways The Lady In Red is the quintessential Roger Corman movie. His wife, Julie Corman, is the named producer, but plays very much from hubby’s textbook.

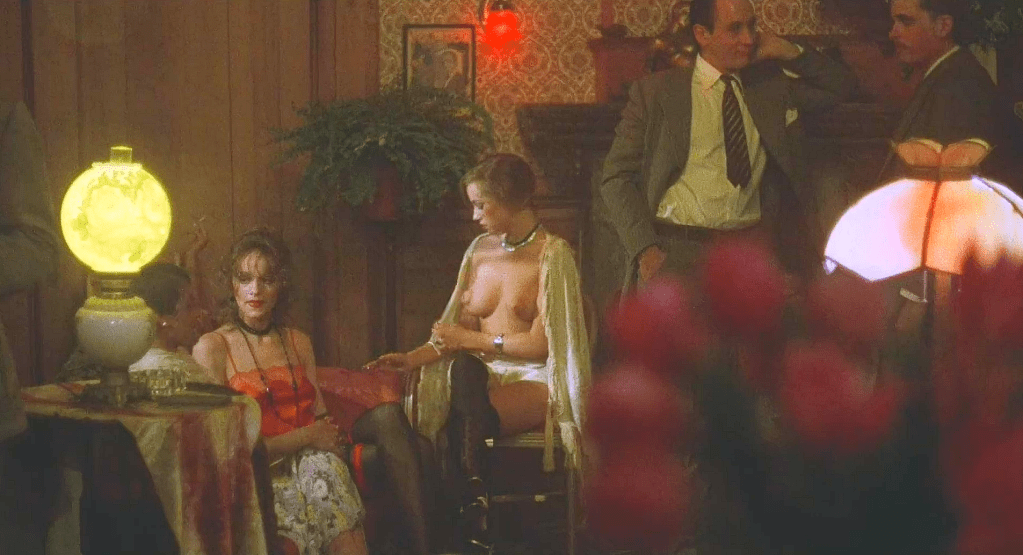

Corman was a true maverick, albeit an eye-wateringly tight one, notorious for cutting corners to get movies in the can on ten day shoots. His frequent advice to the posse of enthusiastic kids he paid cheap, in exchange for a break into the biz, was to cut fast with frequent bursts of nudity or violence every few beats. Keep ’em entertained, so you can slip the message in when no-one’s looking, was the credo.

His own directorial works were frequently liberal wolves in redneck sheep coats; a fierce independence throughout his prolific career bled onto the big screen with anti-establishment sensibilities in movies such as William Shatner racism drama The Intruder (1962) and controversial Peter Fonda biker pic The Wild Angels (1966).

Director Lewis Teague was one of the eager proteges who took the pocketful of red cents and managed to fill the screen using every trick in his master’s handbook. As per classic Cormania, he was fighting against the odds – an insanely tight 20 day shooting schedule made behind the scenes as breathless as the front. The restrictions work in the movie’s favour.

The Lady In Red is a masterclass in efficiency; scenes rampage into the next with nary an establishing shot and tight framing maximises limited sets; hand-me-down clothes, props and vintage cars from other New World gangster pics fill out the background to imply a bigger world than afforded.

A dynamite cast piles on the class. Pamela Sue Martin is incandescent in the lead; inbetween TV success as Nancy Drew and Fallon in Dynasty, she grabs the chance to swear, strip and shoot with uncensored aplomb. Robert Conrad is charming as hell as an irrepressibly cheerful Dillinger, while Louise Fletcher and Christopher Lloyd still sported Oscar kudos from One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) and there’s able support from ever-ready B-movie stalwarts Robert Forster and Dick Miller.

If the grand ambition of the movie would seem to cry out for more lavish treatment, be grateful the ferocious creativity wasn’t diluted with compromises a bigger budget would impose. The Lady In Red rolls with rat-a-tat Tommy gun rhythm – fast, funny, savage, sexy, bold, beautiful. There is power in the artlessness; no time for blandness here, as it outstrips more ostensibly legitimate mainstream films by a country mile.

This classic slice of independent cinema works precisely because it is as independent as its writer, uber-executive and heroine. Polly may end up where she started, hitch-hiking in a farmgirl’s dress, but we need people like her in this world – those gutsy enough not to bend or falter defending the underdog as much as themselves. As she finally gets some well-deserved sleep on the road to California, we can only wish this beautiful dreamer the sweetest dreams.

After all, there’s a lot of red dresses in Hollywood.