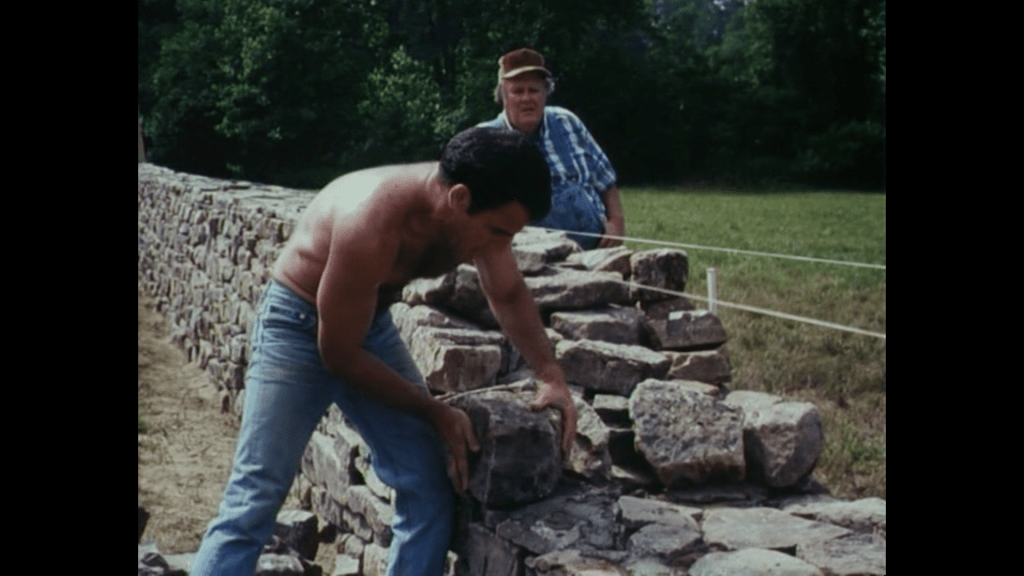

Once the contract is signed, it quickly becomes apparent the men are trapped. Phone calls or outside contacts are banned, the estate is enclosed by towering barbed wire fences. They are prisoners, bound by personal integrity and must complete their dues. The theme of ‘paying the piper’ is highlighted by the pointless nature of the wall. It stands in the middle of an empty field, bordering only open grass. There is no reason for the work, other than the work itself.

Flower and Stone do not visit their serfs or care about the result. They bought a 15th century castle on a trip to Ireland and brought back 10,000 stones (as per the money owed). It is a monument to egotism, to be viewed as “a dirge of the past we carry with us.” For the millionaires, this “wailing wall” is a statement of their success, for the hapless workers a reminder of their failure.

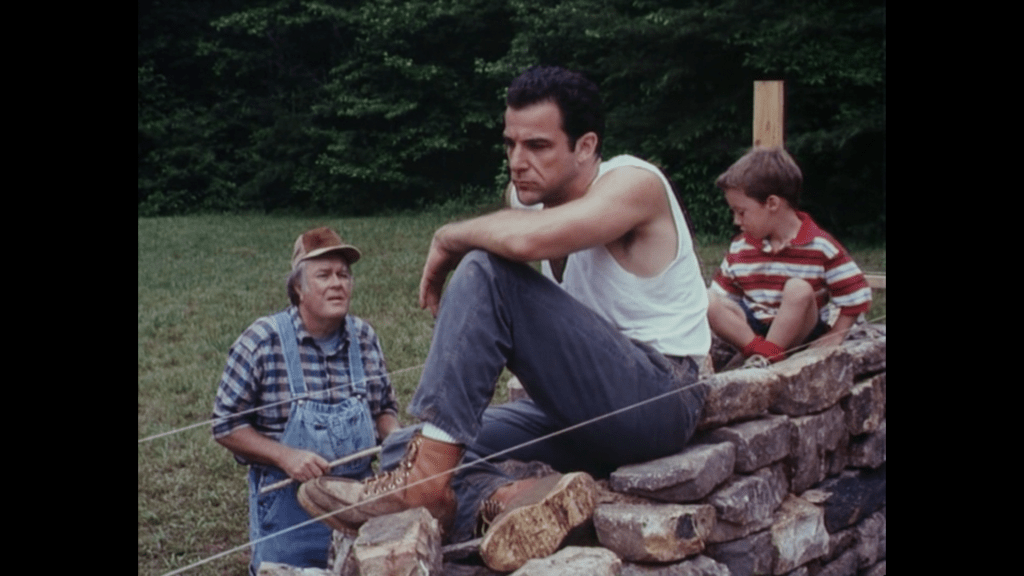

Jim and Jack can redeem themselves only through pain and toil. They are more honourable than their mean-spirited masters in rising to the challenge. These are men without a home, but for a brief period in their self-inflicted prison they form a surrogate family. Jim frequently refers to Jack as “kid” and his parting shot to him is a gem of fatherly advice: “Just remember, brush your teeth after every meal, nothing bad can happen to ya.”

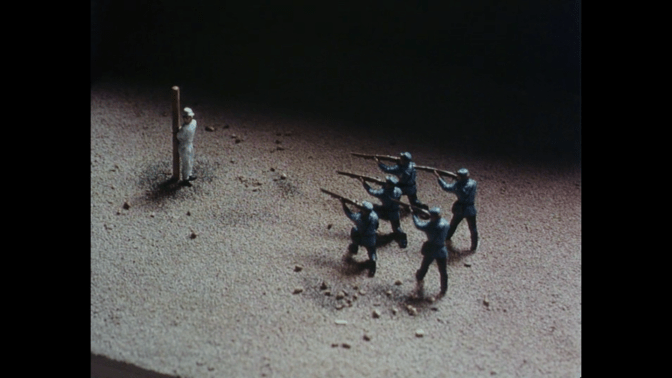

There is a zealot’s sense of justice in their penance. Flower and Stone are playing God with the two men, treating them as pawns in the City of the World. The wall is added to the model landscape as it is being built in reality.

Such power exhibits a sinister edge, foreshadowed by the darker side of the City – toy scenarios display a firing squad and a robber slipping on a banana skin, the perfect analogy that dishonour doesn’t pay. Prisoners are seen to be smiling, happy to work off their punishment, just as Jim and Jack should be, learning from their labour.

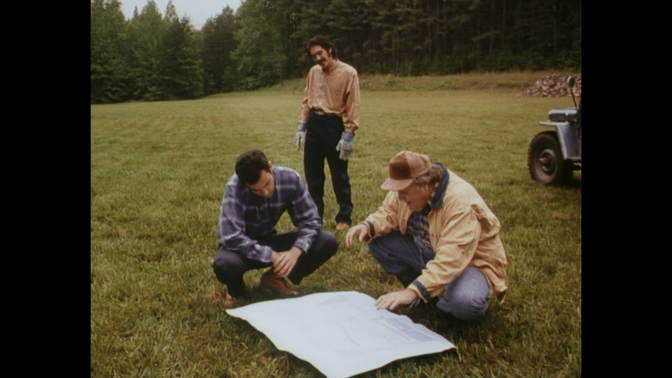

There is a suspicion the two men have been set up, engineered by fate to suffer for the crime of losing. The trailer has already been prepared for them, the stones in place before they arrived, the contracts typed in advance. For Flower and Stone, this was meant to be, so sure is the belief in their decisions. Pozzi and Nashe were destined to be punished for their choices in life. Their handling of the sentence can either strengthen or destroy them, so harsh is the fiscal sword over their heads and brutal the penalty for disobedience.

There is a surreal nature to the material, hewing close to Paul Auster’s original novel, but it is grounded in reality by Philip Haas’ resolutely stripped-down direction. Subtle wit and a measured, hypnotic pace prevent a descent into obvious cartoonishness. There is no need for flashy pyrotechnics here with casting as good as this.

The actors inhabit their roles visually. Everyone physically looks the part. Spader’s wide-eyed, wiry energy as the emotional, foul-mouthed Pozzi contrasts perfectly with Patinkin’s muscular stoicism as the quiet, level-headed Nashe. Durning and Grey as the plump and slight eccentrics play their parts with a sly Machiavellian edge, polite cheer masking a chilling venality. Walsh’s lumbering, drawling old dog Calvin also carries a bite, backed up by Chris Penn’s bruiser stockiness as redneck son, Floyd.

The no-frills approach works in the movie’s favour. The tight budget is spent on a dynamite cast and little else. Director Haas’ subsequent movies (Angels and Insects, Up at the Villa) were more florid, reflecting his alternative career as artist and sculptor, earning renown for ‘The Four Seasons’, exhibited around the world. Ultimately, this is a Paul Auster movie through and through, the simplistic power underlining the novelist’s recurring themes.

The Music of Chance stands as an almost perfect miniature of minimalist cinema, one that lingers long after it ends. The metaphorical nature of the plotting and ambiguity of the twists display a rich understanding of life’s dark tapestry. The future is a lottery, fortune bestowed by a winning ticket, or tarnished by the turn of a card. It is how we react to these challenges or celebrations that define what tomorrow holds. Can integrity help us soldier past defeat?

The cyclical nature of the movie suggests we may be doomed to repeat our mistakes. The symmetry of Flower and Stone’s logic convinces them their actions are justified – everything is for a reason, some of us are blessed, while others are cursed. Do we shape our destiny or does it bend us?

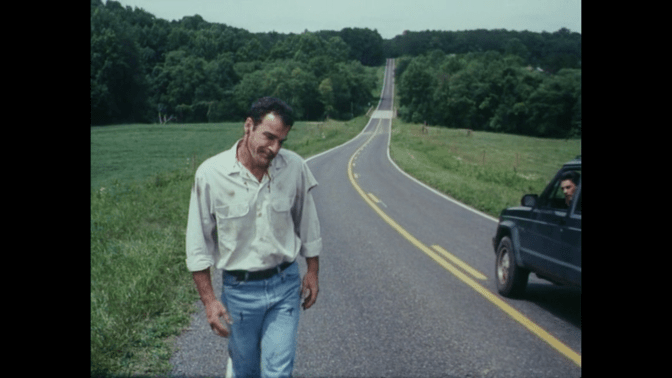

The open ending sees Jim in Jack’s position at the beginning – wandering down the road, bloodied and battered, accepting a lift from a passing motorist to New York. Hints he may finally see his estranged daughter provide hope the experience has tempered his wandering spirit, but who can tell what stones may block his path next?

We never know what the future holds. We only gain a glimmer of understanding when we look back and see how far we’ve come.