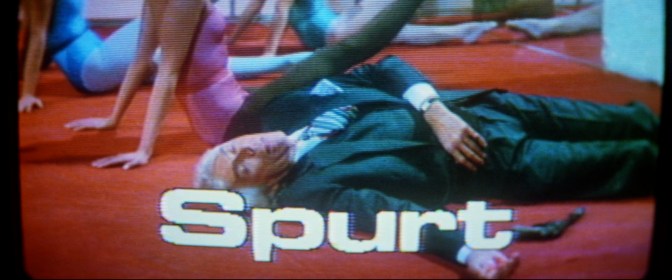

Reston’s nefarious superscheming involves the analysis of viewer reactions to best sell product – precise metrics calculate the exact point to draw the eye and hypnotise the masses into buying that cereal or voting for that president. Far fetched right? In 1981 it was science fiction. After all, no-one is that susceptible in this day and age…

Looker is more satire than straight thriller. Writer/director Michael Crichton delights in twisting genre expectations into stony-faced pastiche, especially with the use of the L.O.O.K.E.R. gun (Light Ocular Oriented Kinetic Emotive Responses – yes, really just an excuse to squeeze in the title) that briefly mesmerises its victims.

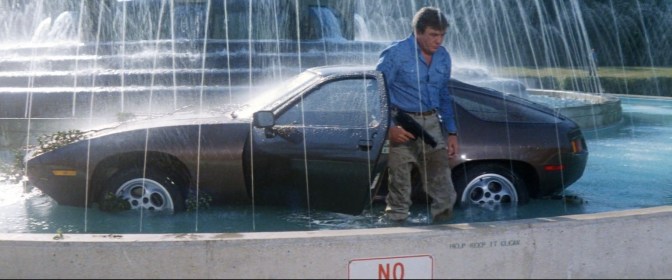

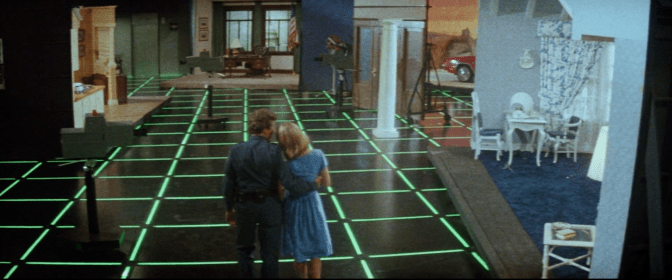

So a car chase, with heroic surgeon and pursuing baddies desperately trying not to look at each other, cuts abruptly to Larry finding himself parked in a fountain. The climatic shoot-out in a virtual TV studio shows the protagonists hiding amongst adverts for cars and kitchens populated by digital families to the hilarity of a braying audience.

The movie falls between two stools. At its best it has the pulp energy and cheeky humour of a pumping B-movie, but the A-list sheen ($12 million budget was high-rank back then) of classic Hollywood. Michael Crichton was coming off his successful adaptation of Robin Cook’s Coma (1978) and the studio suits wanted more of the same, whereas he was more interested in the witty social commentary of his earlier sci-fi/cowboy crossover Westworld (1973).

Crichton is a solid and intelligent director, but his greatest talent was as writer, possessing a true gift for being ahead of the curve in bouncing high science concepts off low human habits. A blockbusting career as novelist (Jurassic Park, Disclosure, Rising Sun et al) remains testament to his prescient talent.

Here, his direction is almost too tasteful, reigning in the potential for exploitation hi-jinks (imagine where Paul Verhoeven would have run with this) which could have pushed the satire to the next level. The movie is terrific high hokum, but wearing a buttoned-up polo shirt the splatter of a good exploding head would have sorted right out.

Looker flopped at the box office, hampered partly by a misleading horror chiller campaign (tagline: If Looks Could Kill). Models murdered by an unseen assassin to a pulsating Carpenteresque synth score aligned it with the stalk-and-slash explosion of the early 80’s, confusing any potential audience.

Not that they were given much of a chance with this one. The suits cut the film heavily, resulting in a cramped 90 minute running time, without allowing space to digest the visionary ideas and stylish wit. It’s always a bad sign when major exposition points are dubbed over filler shots of cars.

If the fun intentions remain anywhere off the cutting room floor, it is in pre-LA Law Susan Dey’s game performance as ‘almost-perfect’ Cindy. She’s the nubile breath of fresh air throughout, bright-eyed and spouting sarcastic one-liners that offset earnestness with sparky aplomb. Dey’s can-do attitude continued off-screen, having to endure lengthy hours standing nude being digitally scanned for then ground-breaking computer modelling, one of the areas Looker’s technological foreshadowing got spot on.

Great science fiction reflects the contemporary world and accelerates it – it can be visionary when right and nostalgic reminder when wrong. Looker is both. Crichton nails our burgeoning obsession with false iconography, but the most chilling aspect of his futureshock warning is the conspiracy plot would be unnecessary in today’s world.

Now, the dangers of media manipulation, computer trickery, airbrushed beauty and needless enhancements are widely reported. We embrace Botox, liposuction, skin peels and fake tan, immersing ourselves in fantasy as confidence boost, forgetting our imperfections reveal true beauty.

The Machiavellian data collections of companies such as Cambridge Analytics and Google are out in the open, but modern society accepts them. Subliminal advertising is rife and we willingly lap it up. Exposing a cover-up elicits the same jaded response as hearing a politician’s easily disproved lies. In this post-truth world, we know we’re being sold, we just don’t care anymore, so long as the falsehood bolsters our own prejudice and desire.

Hell, maybe there is a conspiracy here after all.